Patient population and dataset

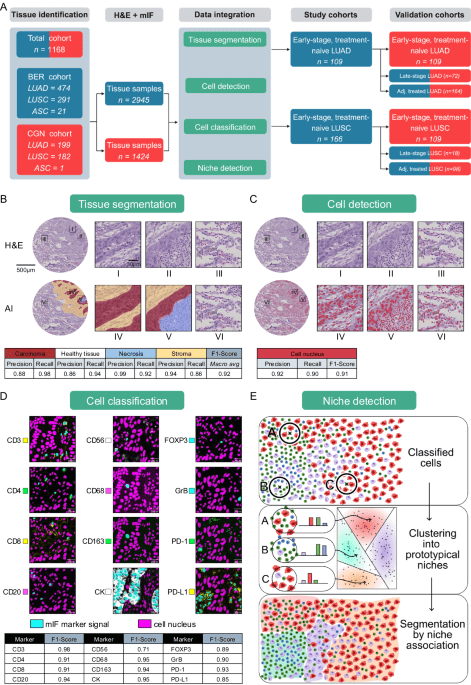

We examined 1168 NSCLC patients treated from 2006 to 2019 at the University Hospital Cologne (n = 382) and Charité Berlin (n = 786), comprising 730 males and 438 females, with a mean age of 66.1 years and a median age of 66.4 years. 346 patients had received adjuvant treatment. We had definite survival times for all but 209 patients that were still alive at the time of analysis and covered observation periods of a maximum of 186 months. We divided NSCLC patients into 673 LUAD, 473 LUSC, and 22 excluded cases with mixed subtype. Diagnoses, histological growth patterns, tumor grading, pTNM classification, angioinvasion, lymphatic invasion, and tumor staging (according to the 8th edition of the TNM classification, AJCC) were reviewed by two board-certified pathologists with over 6 (S.S.) and 10 (F.K.) years of experience in thoracic pathology. Histological subtyping was based on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), Periodic Acid–Schiff (PAS), and Van Gieson staining. Routine diagnostic immunohistochemical panels used for tumor classification included p40, p63, CK5/6, CK7, and TTF-1 (Supplementary Fig. 24). The diagnosis of LUAD was based on the presence of glandular growth patterns and typically showed CK7 positivity and p63/p40 as well as CK5/6 negativity, with or without co-expression of TTF-1. LUSC was diagnosed in the presence of keratinization and/or intercellular bridges in combination with positivity for p40, p63, and CK5/6 and no or only weak CK7 expression. All major histological subtypes77 of invasive non-mucinous adenocarcinoma—namely lepidic, acinar, papillary, micropapillary, and solid patterns—as well as invasive mucinous adenocarcinomas were included in the study (see Supplementary Fig. 24). Rare LUAD variants77, including minimally invasive adenocarcinoma, colloid adenocarcinoma, fetal adenocarcinoma, and enteric-type adenocarcinoma, as well as large cell lung carcinomas were excluded due to low frequency and distinct biological characteristics. Neuroendocrine tumors—identified by positivity for synaptophysin and chromogranin A or CD56—including small cell lung carcinoma (SCLC), large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma, and typical or atypical carcinoids, were excluded from all analyses because they represent a separate tumor group as defined by the WHO.

Rationale for separate analysis of LUAD and LUSC

We performed separate analyses for LUAD and LUSC based on clinicopathological and methodological rationales.

Clinicopathological rationale

LUAD and LUSC are increasingly recognized as distinct tumor entities, based on well-established differences in etiology, histology, and molecular biology:

-

1.

Different etiology: In contrast to other types of lung cancer, LUAD also manifests in non-smokers, particularly in female non-smokers. In contrast, LUSC is strongly associated with smoking78.

-

2.

Different origin: LUSC typically arises from a main or lobar bronchus, with approximately two-thirds of cases occurring in the central lung compartment. In contrast, LUAD is more frequently observed in peripheral regions77.

-

3.

Different pathogenesis: The atypical adenomatous hyperplasia and adenocarcinoma in situ, which originate from type II pneumocytes and/or club cells, are regarded as the precursors of invasive LUAD79,80. In contrast, squamous dysplasia and squamous carcinoma in situ are considered to be the precursors of LUSC, which arise in the bronchial epithelium77.

-

4.

Different histology: The histomorphology of LUAD and LUSC is markedly disparate, exhibiting distinct cytomorphology, growth patterns, and immunohistochemical expression profiles81,82,83.

-

5.

Different molecular landscape: LUAD and LUSC exhibit markedly disparate molecular signatures84,85. For instance, several oncogenic driver gene alterations, such as EGFR or ALK have been identified in LUAD, which are typically not present in LUSC.

-

6.

Different treatment effects: Some targeted agents developed for LUAD have been shown to be largely ineffective against LUSC. In addition, studies have shown that the survival benefit of IO therapy is histology-dependent86.

Methodological rationale

Joint niche discovery would have required assuming shared spatial biology between LUAD and LUSC, potentially obscuring subtype-specific patterns. To preserve biological resolution, we performed niche discovery separately. For comparability, we aligned niches post hoc at the phenotype level using partial optimal transport to identify matched niche pairs across subtypes (see also “Methods”, p. 37).

Tissue microarray construction and staining

For each patient, 4 cores of 1.5 mm diameter representative tumor tissue were taken and placed on TMA slides, each containing a tonsil stain as a positive control for staining success and spot to patient mapping verification. TMAs were stained with an antibody panel for use in multiplex immunofluorescence imaging by Ultivue (Cambridge, MA).

The 12-plex immunofluorescence panel was designed to capture multiple immune cell phenotypes present in the NSCLC TME (pan-cytokeratin [panCK], CD3, CD8, CD68, CD20, CD4, FoxP3, PD-1, PD-L1, CD56, CD163, GranzymeB). Multiplex immunofluorescence (mIF) staining was performed on 2 µm sections of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue blocks of NSCLC TMA on the Leica Bond RX autostainer as previously described in Vasaturo et al.87. In brief, FFPE samples are dewaxed, and epitope retrieval is performed. After blocking, the slides are incubated with DNA-barcoded primary antibodies. All antibodies were provided in pre-optimized Ultivue kits and were diluted 1:100 in antibody diluent according to the manufacturer’s standard protocol. All the targets are simultaneously amplified to increase assay sensitivity, and then, for each barcode, a complementary oligonucleotide probe tagged with a fluorescent dye is used to label the antibody conjugates. Different fluorophores are associated with each barcode–probe pair to spectrally separate the targets during imaging. High-plex panels require an Ultivue proprietary process, termed “exchange”, which gently removes the fluorescent signal by dehybridizing the first set of four probes, while leaving the conjugated antibodies intact and bound to the tissue for detection by a second set of probes. A 12-plex assay thus consists of three image detection rounds using four probes per round, generating 4 × 3 images of the same tissue using the AxioScan Z1 whole slide scanner. Since tissue spots can change position during the different scanning phases, we collected per-spot ROI annotations of each TMA to ensure that each spot is assigned to the right patient information. Splitting the TMAs into individual spot images greatly facilitated later image registration efforts. Registration was based on a DAPI signal that was contained in each scan group.

In total, the resulting dataset comprised a total of 57,000 microscopy images with an average size of 8650 × 8350 for the mIF channels and 17300 × 16700 for the H&E slide, representing a region of around 1.76 square millimeters each.

|

Antibodies |

Company |

Identifier |

Dilution |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Anti-human CD3 |

BioCare |

ACI 3170 A |

1:100 |

|

Anti-human CD4 |

Abcam |

ab238798 |

1:100 |

|

Anti-human CD8 |

BioCare |

ACI3160CF |

1:100 |

|

Anti-human CD20 |

Thermo/eBio |

14-0202-82 |

1:100 |

|

Anti-human CD56 |

Thermo/eBio |

701379 |

1:100 |

|

Anti-human CD68 |

BioCare |

CM033CF |

1:100 |

|

Anti-human CD163 |

Abcam |

ab213612 |

1:100 |

|

Anti-human FoxP3 |

Thermo/eBio |

14-4777-82 |

1:100 |

|

Anti-human PanCK |

Bethyl/Fortis |

PGS170523 |

1:100 |

|

Anti-human PD-1 |

Abcam |

ab251613 |

1:100 |

|

Anit-human PD-L1 |

Abcam |

ab226766 |

1:100 |

|

Granzyme B |

Abcam |

ab214443 |

1:100 |

Contact for reagent and resource sharing

Additional information and requests for reagents should be directed to Ultivue (https://ultivue.com).

Imaging quality control

A pathologist reviewed each of the 4400 H&E scans to ensure that spots with tissue damages and tears, that potentially occur during staining, are rejected from further analysis, affecting around 10% of data. For each mIF-channel, the intensity histograms of all spots were collected and analyzed with a local outlier factor analysis as implemented in scikit-learn to highlight potential glow-artifacts and auto-fluorescence. The top 1% highest scoring tissue spots were inspected for rejection bty a pathologist, affecting less than 0.1% of data that was dropped from further analysis.

Registration and tissue alignment quantification

For every tissue spot, each mIF scan group of four channels was registered to the H&E baseline using the DAPI nuclear expression signal as a guide. We employed a proprietary registration algorithm developed by Aignostics and applied it at full gigapixel resolution to enable cell-level registration. We limit the registration to basic geometric adjustments—specifically, affine transformations—to facilitate interpretability and avoid the generation of artifacts that would be infeasible to review manually with the amount of data available.

The quality of tissue alignment was scored computationally on a per-pixel level to allow rejection of areas where cells do not align well enough after registration, which can occur due to mechanical damage introduced between scanning phases. A subset of twenty spots containing misaligned regions was annotated to train and test the alignment mask quality control (QC) method proprietary to Aignostics. Spots with less than 0.7 square millimeters of aligned tissue were rejected for a lack of content. Spots with more than 3 square millimeters of aligned tissue were rejected from further analysis as the spots were broken into several shards that distort their spatial statistics.

Statistics and reproducibility

Analyses were performed in Python 3.11.9 with pandas 2.3.2, numpy 2.3.2, scipy 1.16.2, lifelines 0.30.0, scikit-learn 1.7.2, and seaborn 0.13.2. Cellular graphics were prepared using Inkscape 1.3.2. In a first step, we extract the biological structure that is contained in the pixel space, which we call the image analysis pipeline. In a second step, the raw biological structures are summarized based on their spatial composition to create interpretable features. In a third step, we build predictive models for survival outcomes based on the spatial features.

Step 1: Image analysis pipeline

Tissue segmentation

Although the tissue cores were punched from wider tumor regions, considering the whole spot as a tumor would be imprecise. In particular, necrosis and healthy tissue areas should be excluded when calculating the density of immune cells infiltrating the tumor. Therefore, we created a tissue segmentation model to distinguish carcinoma, stroma, necrosis and healthy areas. A total of 10871 tissue polygons were annotated, 697 for healthy, 4672 for carcinoma, 4571 for stroma and 931 for necrosis. We trained an ensemble of UNets31 on a mixture of weighted cross entropy and DICE loss and collected the average F1 score obtained from a five-fold cross-validation, where the hold-out spots were selected based on the patient indicator.

Cell detection

We annotated 100,000 cell nucleus polygons to train and validate a StarDist model using the public repository version 0.8.2 commit id 466d0c on H&E-stained images at 20x resolution. The model employed the U-Net architecture and a star-convex polygon prediction framework, which we found to be particularly data-efficient. Recall and precision metrics were computed for 20 tissue spots, each exhaustively annotated over 100 μm² regions of interest.

Cell classification

A board-certified pathologist annotated a subset of the previously detected cells for marker positivity in each of the mIF channels separately. The labels were collected sparsely with an emphasis on spatial heterogeneity and local contrast of positive and negative pairs. We trained twelve independent binary models as they have to adjust to either attending to nuclear or membranous stains, have to consider the surrounding tissue contexts differently and have to suppress channel-specific artifact types and auto-fluorescence levels. To this end, we used a ConvNeXt Base33 and provided it with a 256 square pixel crop centered on the cell to be classified at 10x magnification, together with the binary label from the pathologist. We only provided the H&E and respective mIF channel to classify, as preliminary experiments indicated a strong tendency for Clever Hans34,88,89,90 overfitting if the model is presented with all mIF channels simultaneously. We repeated training on 5 folds to gather cross-validation scores and joined the models into an ensemble for inference on the whole cohort to further increase the performance for the following analysis. We distributed the inference of the 12 binary tasks with 3 ensemble members each applied to 53 million cells on a Kubernetes cluster, as required due to the total amount of 1.5 billion images.

Co-registration of H&E and mIF images

H&E and mIF staining were performed sequentially on the same section (for details, see “methods”). This is a critical prerequisite and allows for registration/alignment of the resulting images as well as the integration of model annotations on a single cell level. The H&E-based and mIF-based models, although optimized separately, were combined to work together as the H&E and mIF stainings were co-registered/spatially aligned (Fig. 6 provides an example of an alignment result between H&E and mIF). As a result, annotations generated by one algorithm in the H&E domain are seamlessly linked to annotations generated on the mIF domain. This alignment provides an integrated view of the TME, with H&E providing a robust basis for tissue segmentation and cell detection, and mIF adding detailed cell classification based on immuno-staining patterns.

Motivation for training multiple binary classification models

In the mIF domain, we trained individual binary classification models for each stain to optimize detection accuracies due to the unique patterns associated with each marker. Each stain required a different model (1) due to the different localization (nucleus, cytoplasm, membrane), which significantly affects the detection process, and (2) stain-specific imaging artifacts, such as speckle noise or blurred fluorescence, which must be accounted for to avoid false positives. During training, model performance was closely monitored on a hold-out validation set. This approach enabled us to achieve highly accurate results for each stain, ensuring that the detection and classification process was robust and adaptable to varying image conditions. These models were then applied to the whole cohort and offer improved performance compared to standard methods (see comparison with StarDist; Supplementary Fig. 4, Supplementary Table 1).

Integration of H&E and mIF data

Both the H&E and mIF models are the basis of the downstream analyses, including niche generation and survival prediction. The integration is required for two reasons. (1) The H&E-based model enables tissue-level segmentation into carcinoma, stroma, necrosis, and non-neoplastic regions, thereby ensuring that the analysis focuses on histologically relevant compartments. This kind of spatial annotation cannot be reliably obtained from mIF alone due to its limited morphological information. mIF, in turn, contributes precise cell-type classification through antigen-specific labeling, which is essential for phenotypic resolution. (2) The combined use of H&E and mIF is particularly critical for distinguishing morphologically similar cell types. For example, carcinoma cells and normal epithelial cells, such as pneumocytes or ciliated epithelial cells, often share expression of epithelial markers (e.g., cytokeratins), making them difficult to differentiate using mIF alone. Here, the morphological features captured by H&E—such as nuclear atypia, cell shape, and architectural arrangement—are used for accurate classification. Conversely, certain immune cell subtypes (e.g., B vs. T lymphocytes) are indistinguishable based on H&E but can be clearly resolved using mIF markers such as CD20 and CD3. Thus, the integration of both modalities provides complementary strengths: H&E delivers detailed tissue architecture and tumor morphology, while mIF enables high-resolution immunophenotyping. Together, they allow robust and context-aware cell classification across diverse tissue environments. A key feature of our approach is the cross-domain integration of these models for the characterization of cell niches. Cell niches are defined as distinct cellular neighborhoods within a 34 micron radius.

Integration of all data modalities for survival analysis

Survival analysis builds on these niche descriptions, incorporating them into a multivariate model alongside clinical metadata such as UICC staging. The detailed cellular composition of the niches, as generated by the integrated H&E and mIF models, provides a biologically meaningful context in combination with clinical metadata and is used to predict survival.

Step 2: Extraction of spatial composition

Marker density in tumor

We computed the density of positive cells for each marker within the total tissue area and the tumor region, respectively. The total tissue was defined as the union of all tissue segmentation masks and the tissue alignment QC masks, effectively excluding only the white-background and damaged tissue. The tumor region was defined as the union of the tissue alignment QC mask and the tissue segmentation results for carcinoma and stroma. Measurements are scaled to cell counts per millimeter and provided as log1p-densities for any further numerical evaluation, as motivated by the strong right skew of the distribution. Further analyses comprised 2233 tumor samples from 663 patients (303 female, 360 male; mean age = 64.7 years; median age = 64.7 years; Fig. 2A, E) and 1657 tumor samples from 462 patients (116 female, 346 male; mean age = 67.8 years; median age = 68.7 years; Fig. 2B, G).

Cell niches clustering

While exact biological definitions of niche sizes do not exist, we oriented our niche size definition by the smallest and largest immune cells occurring in the TME85,86. In particular, we used the macrophage, for which a diameter of up to 30 µm has been documented87 as the upper size limit. The lymphocyte, which typically has a minimal diameter of 8 µm, was used as the lower limit87,89. Considering the lymphocyte as the most frequent and smallest cell at the niche center, a 34 µm radius would allow for at least one adjacent macrophage, but also higher order neighbors, given the smaller lymphocyte sizes. This is consistent with parallel work using interaction ranges of 30–40 µm, such as Risom, Keren or Stoltzfus et al.30,62,63.

Using the predefined radius of 34 µm, we used a scipy KDTree91 to calculate the number of cells positive for each marker within this spatial neighborhood (see “Methods” section: Cell classification, page 33). These marker counts were logarithmically transformed to put more weight on the presence or absence of cells by gradually saturating the contribution, increasing count, to further put an emphasis on the relative composition of a neighborhood the expression values were divided by the local mass (percentage). To identify unique cellular neighborhoods, we performed Mini Batch K Means + + clustering92 with a batch size of 8000 to define 10 prototypical neighborhoods from the 53 million extracted histograms. Each cell was then assigned to the closest prototype using nearest-neighbor classification. We subsequently aggregated the data for each tissue spot to quantify how many cells corresponded to each identified niche. Further analyses comprised 2233 tumor samples from 663 patients (303 female, 360 male; mean age = 64.7 years; median age = 64.7 years; Figs. 3L, N, 5A) and 1657 tumor samples from 462 patients (116 female, 346 male; mean age = 67.8 years; median age = 68.7 years; Figs. 4L, N and 5B).

Step 3: Predictive model

Propensity score-matching

The following motivates and documents the technical implementation of propensity score-matching, a method to balance patient characteristics between studies.

We carefully checked the compatibility of the training and validation cohorts before checking the transferability of the immunological characterization using a statistical pre-screening approach. This approach aimed to detect potential distributional shifts unrelated to the immunological characterization under investigation and thus aims to increase the reliability of our results.

First, we assessed cohort compatibility by training a classifier based on basic patient metadata, including UICC8 (integer number), observed overall survival (real number) and censoring event (Boolean value). The task of the classifier was to predict the origin of the patients (Berlin or Cologne). When the classifier could accurately predict a patient’s location based on metadata alone, it indicated the presence of a particular patient stratum in one cohort but not in the other. Specifically, for LUAD cases, we obtained a non-chance F1 score indicating a distributional shift of key metadata between cohorts.

In response to this finding, we propose to remove unrelated cases from the training cohort (Berlin) while leaving the test cohort untouched. To achieve sample stratification, we use propensity score matching based solely on metadata, including UICC8, overall survival and censoring. Our approach uses a nearest neighbor-based algorithm for optimal complete matching. Specifically, we train a classifier to predict the treatment location (Berlin or Cologne) for each patient and use the model’s logits to identify the most similar patient from Berlin for each Cologne patient. Importantly, we perform sampling without replacement to ensure that each patient is used only once.

Maximum relevance minimum redundancy selection

We follow a maximum relevance minimum redundancy criterion93 for feature selection, which we adapt for censored survival data. For each candidate feature, we fit a univariate Cox regression92 and consider the achieved training set c-index as the feature’s relevance. The feature with the highest relevance is picked first. The subsequent choices are guided by prioritizing high-relevance features but discouraging redundancy with respect to the already chosen features. To this end, we compute the cross-correlation between each candidate feature and the previously picked features and treat the absolute value of the average as a measure of redundancy. The candidate features are then sorted by the difference between the relevance score and the redundancy score. The first candidate is taken as the next choice, and the process repeats. Our implementation requires setting a maximum number of features to consider and is treated as a hyperparameter to be tuned in an inner fold cross-validation, for which we have integrated our implementation with sklearn92.

Maximum risk score approach

The maximum risk approach is motivated by the following reasoning: In conventional or AI-based biomarker studies or histopathological diagnostics to evaluate tumor aggressiveness, e.g., for histological grading and Ki67 immunohistochemistry, the evaluation of many biomarkers follows a so-called “hot-spot” strategy and does not use averages even if large resection specimens on whole slides are available94,95,96,97. For instance, tumor grading mostly does not rely on averages, but renders a diagnosis based on the presence of the features associated with the highest risk of disease progression. This means that a tumor is diagnosed as “high grade”, even if the majority of the tumor shows “low grade” morphology and only a subregion shows “high grade” features.

We used maximum risk scores, because the purpose of our approach was to identify patients having an increased risk with high sensitivity in order to ensure that the niche-based patient stratification will not lead to withholding a necessary adjuvant therapy.

Survival analysis

The curation of a representative and homogenous patient cohort is crucial for survival analysis, especially in observational studies, to ensure that main effects are not biased by distributional shifts within the cohort. In our main results, we focused on the analysis of early-stage patients, with a separate analysis for late-stage (UICC8 = 4) to be found in the Appendix. We also remove patients with r-status = 1, meaning that patients for whom complete tumor removal could not be confirmed. In addition, we removed patients whose observed or censored survival was less than three months, as their death can also be attributed to complications during or after surgery, limiting their usefulness for gaining insights into cancer immunology. Another notable distributional shift may result from treatment with adjuvant therapy, which we therefore present in a separate analysis in the Appendix. The patient numbers in Fig. 1A reflect the selection criteria introduced here.

Patients are represented by up to four tissue spots. We analyzed them using a multiple instance learning approach and chose a late fusion strategy for better interpretability. In this approach, each spot was evaluated individually for survival based on its niche composition features, and the model outputs a continuous risk score (logit) for each spot. To derive a patient-level risk estimate, we applied max-pooling across all spot-level outputs—meaning the highest risk score among a patient’s spots determines the overall risk classification (“hot-spot approach”). This reflects the clinical rationale that the most aggressive region within the tumor is most prognostically relevant. The final patient-level prediction is thus determined by the maximum risk score across all available spots.

The cellomics features are typically right-skewed with a heavy tail, which motivates the use of a non-linear normalization transform to better comply with the assumption of the following regression modeling. Instead of employing a fixed log1p transformation, as is often used in omics pipelines, we opt for the power transformation of yeo-johnson98 on the respective training for the increased flexibility. Inner fold cross-validation was used to tune sweep over a number of features to select, and a range of alpha regularization and select the best combination based on the average multiple-instance c-index. To assess the improvement in outcome prediction of the cell niche model compared to the clinical baseline (UICC8), we computed the relative improvement in c-index, accounting for its informative range between 0.5 (random prediction) and 1.0 (perfect prediction). It is defined as follows:

$${{{\rm{Relative}}}}\; {{{\rm{improvement}}}}=\frac{c-{model}-0.5}{c-{baseline}-0.5}$$

(Eq. 1)

where c-model denotes the c-index of the cell niche model, c-baseline is the c-index of the clinical baseline (UICC8), and 0.5 represents the lower bound of the c-index, corresponding to random prediction.

The cox regression trained on Berlin is then applied to the patients from Cologne. We collected the risk attributions generated by the Cox regression model and stratified the test cohort into three groups based on the distribution of these scores. Specifically, we divided the patients into tertiles corresponding to the lower, middle, and upper thirds of predicted risk. These three groups are referred to in the main text as risk strata RS1 (low risk), RS2 (intermediate risk), and RS3 (high risk). This post-hoc discretization was introduced to enhance the interpretability of the survival analysis and visualization, while maintaining the model’s continuous output during training and inference. The use of three risk groups provides a natural counterpart to the UICC clinical staging system for early stage lung cancer (stages I–III), according to which patients in our study were classified. This alignment facilitates integration with established staging frameworks and enhances clinical interpretability. Stratifying patients into low, intermediate, and high-risk groups is also a widely used and practical approach across cancer types, including lung, prostate, and breast cancer. Compared to a simple low/high split, the three-tiered system offers more nuanced risk assessment while remaining actionable in routine care and clinical trial design. Kaplan-Meier curves are tested for statistically significant separation among the patient strata using log-rank tests99. Demographic details of the analyzed patient subsets are as follows: Fig. 6A–C comprises 109 patients (45 female, 64 male; mean age = 64.7 years; median age = 65.4 years). Figure 6D includes RS1 (n = 61; 29 female, 32 male; mean = 64.3; median = 64.0), RS2 + 3 (n = 163; 64 female, 99 male; mean = 65.8; median = 66.1), and UICC I (n = 148; 66 female, 82 male; mean = 65.2; median = 64.8). Figure 7A–C represent 109 patients (24 female, 85 male; mean age = 69.9 years; median age = 70.4 years), and Fig. 7D includes RS1 (n = 66; 20 female, 46 male; mean = 69.0; median = 69.9), RS2 + 3 (n = 209; 54 female, 155 male; mean = 69.3; median = 70.3), and UICC I (n = 163; 49 female, 114 male; mean = 69.3; median = 70.2). The corresponding Supplementary analyses comprise: Supplementary Fig. 12A, B (109 patients; 45 female, 64 male; mean = 64.7; median = 65.4), Supplementary Fig. 13A, B (109 patients; 24 female, 85 male; mean = 69.9; median = 70.4), Supplementary Fig. 14A (n = 72; 39 female, 33 male; mean = 62.5; median = 61.6), Supplementary Fig. 14B (n = 18; 6 female, 12 male; mean = 68.0; median = 68.8), Supplementary Fig. 15A (n = 164; 75 female, 89 male; mean = 64.4; median = 64.1), and Supplementary Fig. 15B (n = 98; 18 female, 80 male; mean = 64.1; median = 63.6).

Immunology phenotype loading

The marker panel was selected with the aim to assess in addition to the cancer cells the distribution of the main immune cell populations (e.g., T cells, TAMs, B cells, and NK cells) according to established lineage markers (e.g., CK, CD3, CD68, CD20, CD56, CD4, CD8), which have been described to be present in the TME of LUAD and LUSC22. The remaining markers were selected to determine the activation state and the cytotoxic or immunosuppressive potential of the cells (e.g., PD-1, FoxP3, PD-L1, CD163).

A complete analysis of all 212 = 4096 theoretically possible combinations from the 12 selected markers would not be meaningful since many marker combinations are not present physiologically. For this reason, we set up a table with phenotype definitions (Supplementary Data 2), in which we firstly list the main cell populations. Secondly, we subcategorized the main populations in well described immune cell subpopulations (such as CD4 + , CD8 + , and regulatory (FoxP3 + ) T cells or TAM1 and TAM2). We next used the markers granzyme B and PD-1 to allocate lymphocytes as activated. With the expression of PD-1 only, we classified the lymphocytes as exhausted. PD-L1 expression—independent of the cell lineage—was used to subclassify cells as immunosuppressive. No additional subpopulations were defined from combinations of those cell populations and markers whose biological relevance is currently unknown, e.g., the expression of CD4 and/ or CD8 expression in TAMs.

For easier interpretability, the aim of our classification was also to avoid populations without known biological roles. Furthermore, we attempted to limit the fragmentation of our classification because too many populations would increase the risk of overfitting the machine learning model. This approach yielded 23 medium-grained or 43 fine-grained cell phenotypes. Examples of all 43 fine-grained cell phenotypes along their marker expression are shown in Supplementary Fig. 3.

LUAD and LUSC, matched niches based on phenotyping

We employ partial optimal transport64,65 to quantitatively determine matched pairs among the independently derived niches in LUAD and LUSC. The niches are characterized by the distribution of phenotypes they encompass. To measure the similarity of categorical distributions, the chi-squared test is often used, and serves us as a distance measure for the identification of analogous niches. We adopt the symmetric distance formula from the chi-squared kernel100

$${\sum}_{i}\frac{{(\,{x}_{i}\,-\,{y}_{i\,})}^{2}}{(\,{x}_{i\,}+\,{y}_{i})}$$

(Eq. 2)

Since the number of matching pairs is not known a priori, we systematically evaluated all scenarios ranging from zero matches to full matches (10/10). Following best practices in clustering and dimensionality reduction, we assume an “elbow” phenomenon that describes the transition from easily matched pairs to more difficult matches. Therefore, we analyze the log transport costs to identify this characteristic pattern.

Step 4 – Orthogonal validation

Cell classification—in-house optimized versus standard StarDist

We compared the performance of our model against publicly available baseline checkpoints, referred to as the “Standard StarDist H&E model” and the “standard StarDist DAPI model.” For each model, F1-scores were calculated on the 20 test tissue core regions of interest. Differences in average F1-scores were assessed for statistical significance using a one-sided paired-sample permutation test with 9999 iterations.

Immunohistochemical based validation of mIF derived PD-L1 scoring

We validate the mIF based quantification of the PD-L1 state with an orthogonal protocol based on immuno- histochemistry brightfield microscopy and manual scoring from expert pathologists. The corresponding patient subset comprised n = 769 (301 female, 468 male; mean age = 65.7 years; median age = 66.3 years).

For this, TMA blocks were sectioned at a thickness of 4 μm for immunohistochemical analysis. The sections were incubated in CC1 mild buffer (Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, AZ, USA) at 100 °C for 30 min. Afterward, they were treated with an anti-PD-L1 antibody (E1L3N, Cell Signaling, #13684S, 1:200) at room temperature for 60 min and visualized using the avidin–biotin complex method with DAB staining. The BenchMark XT immunostainer (Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, AZ, USA) was used for these steps. Cell nuclei were counterstained with hematoxylin and bluing reagent (Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, AZ) for 12 min.

The stained sections were analyzed under an Olympus BX50 microscope (Olympus Europe), and the tumor proportion score (TPS) was calculated as the percentage of PD-L1-positive tumor cells among all viable tumor cells. TPS scoring was performed independently by two pathologists (S.S. and F.K.), who have 8 and 14 years of experience in lung pathology, respectively. Digital histological images were captured using the PANNORAMIC 1000 slide scanner (3DHISTECH).

To assess the precision of the AI-powered approach in identifying prognostically relevant immune states within the TME, a correlation analysis was performed between the TPS scores obtained through multiplex immunofluorescence (mIF) by the AI approach and those determined via immunohistochemistry (IHC) by the pathologists (Supplementary Fig. 6). The correlation was tested for statistical significance using scipy.stats.pearson_r.

H&E based validation of mIF derived lymphocyte counts

We validated the multiplex immunofluorescence (mIF)-based quantification of lymphocytes by comparing it with an independent H&E-based quantification using a state-of-the-art foundation model. The corresponding patient subset comprised n = 1125 (419 female, 706 male; mean age = 66.0 years; median age = 66.3 years). For this purpose, we employ an in-house variant of RudolfV101, fine-tuned for cell classification. The number of lymphocytes detected is compared to the number of CD3- or CD20-positive cells identified in mIF on a tissue core-by-tissue core basis (Supplementary Fig. 7).

Given the heavily right-skewed distribution of cell counts per tissue core, the data are log-transformed prior to analysis. This transformation normalizes the distribution and ensures the validity of the subsequent statistical test. Statistical significance of the correlation between the two methods is assessed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient, implemented via scipy.stats.pearson_r.

Risk score heterogeneity and resection based validation of TMA derived risk quantification

To evaluate the adequacy of TMAs for risk score assessment, we analyzed inter- and intra-tumoral heterogeneity of niche-based risk scores across tissue cores from each patient and throughout the cohort. The analysis included 2233 tumor samples from 663 LUAD patients (303 female, 360 male; mean age = 64.7 years; median age = 64.7 years) (Supplementary Fig. 20 A, C, D, F) and 1657 tumor samples from 462 LUSC patients (116 female, 346 male; mean age = 67.8 years; median age = 68.7 years) (Supplementary Fig. 20B, C, E, G).

We further evaluated the reliability of TMA cores as surrogates for whole tumor sections by comparing case risks derived from surgical whole tissue sections with those from their corresponding TMA cores. Each resection is processed through the same pipeline, comprising registration, tissue segmentation, cell detection, cell classification, neighborhood aggregation, and cell-niche assignment. The analyses were conducted on two representative subsets of the main NSCLC cohort. Figure 8D and Supplementary Fig. 23A, B include n = 10 patients (6 female, 4 male; mean age = 68.1 years; median age = 68.0 years), while Fig. 8H and Supplementary Fig. 23C, D include another n = 10 patients (3 female, 7 male; mean age = 69.8 years; median age = 74.0 years).

The segmentation model subsets the resection to tumor-stroma microenvironment regions, excluding other tissue types such as healthy, necrotic, or fatty tissue. The risk model, which links UICC8 staging and niche composition to tissue-core risk scores, is applied to the entire tumor region on a sliding window basis. Specifically, virtual tissue cores are placed to exhaustively cover the tumor area, and risk scores are aggregated across all virtual cores. The case risk for whole tissue sections, as for TMA cores, is defined as the maximum risk score among all virtual cores.

To assess reliability, we evaluate whether the risk conclusions derived from virtual cores of a resection align with those from the subset of TMA tissue cores. Concordance between whole resection-based and TMA core-based risk evaluations is tested for statistical significance using Pearson’s correlation coefficient, implemented via scipy.stats.pearson_r.

Association of risk scores with known mutations and covariates

We obtained panel sequencing data (18 genes) for a subset of LUAD- and LUSC-patients (Supplementary Fig. 16A). The LUAD subset comprised n = 147 patients (63 female, 84 male; mean age = 65.4 years; median age = 65.9 years), and the LUSC subset comprised n = 178 patients (42 female, 136 male; mean age = 69.6 years; median age = 71.0 years; Supplementary Data 7). Statistical significance was evaluated by constructing contingency tables for each gene, with rows representing mutation status (mutated vs. wild type) and columns representing risk categories (e.g., low, mid, high). A chi-squared test was then applied to each table. Our analysis showed no significant correlation between the derived risk scores and mutations in any of the frequently mutated genes in LUAD (Supplementary Fig. 16B) or LUSC (Supplementary Fig. 16B).

Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that additional covariates, including sex, age, ECOG performance status, smoking status, tumor grade, thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1) expression, and growth pattern, are associated with patient survival in early-stage NSCLC. We therefore conducted an analysis to determine whether there were any potential correlations between TME risk profiles and these covariates. Our analysis showed no significant correlation between the derived risk scores and covariates (Supplementary Fig. 17). The analysis comprised the following patient subsets: Supplementary Fig. 17A, B (n = 224; 93 female, 131 male; mean age = 65.4 years; median = 65.7), 17 C (n = 194; 85 female, 109 male; mean = 65.1; median = 65.4), 17D (n = 131; 58 female, 73 male; mean = 65.8; median = 65.9), 17E (n = 211; 88 female, 123 male; mean = 65.7; median = 65.7), 17 F (n = 180; 70 female, 110 male; mean = 65.4; median = 65.8), 17 G (n = 216; 90 female, 126 male; mean = 65.5; median = 65.7), 17H + I (n = 275; 74 female, 201 male; mean = 69.2; median = 70.3), 17 J (n = 234; 61 female, 173 male; mean = 69.3; median = 70.5), 17 K (n = 156; 46 female, 110 male; mean = 68.6; median = 69.9), 17 L (n = 256; 67 female, 189 male; mean = 69.3; median = 70.3), and 17 M (n = 270; 71 female, 199 male; mean = 69.2; median = 70.3).

Association of risk scores with fibroblast abundance

Fibroblasts were detected in H&E-stained images using the RudolfV101 pathology foundation model. The model was applied to all tissue spots in the LUAD (2189 tumor samples from 663 patients (303 female, 360 male; mean age = 64.7 years; median age = 64.7 years; Supplementary Fig. 18C–F) and LUSC (1618 tumor samples from 462 patients (116 female, 346 male; mean age = 67.8 years; median age = 68.7 years; Supplementary Fig. 19C–F) cohorts. For each patient, fibroblast abundance was quantified per spatial niche both as absolute counts and as proportions relative to all cells within the niche. Correlations between fibroblast abundance and niche frequencies were computed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Differences in fibroblast abundance between “hot” and “cold” niches were assessed using a Chi-squared test. To evaluate prognostic associations, patients were stratified into tertiles based on either their fibroblast maximum abundance over tissue spots (max pooling) or their fibroblast mean abundance over tissue spots, analogous to the risk score analyses for niche patterns. Survival differences between strata were analysed using Kaplan–Meier curves and log-rank tests. The LUAD survival cohort comprised n = 108 patients (44 female, 64 male; mean age = 64.7 years; median age = 65.4 years; Supplementary Fig. 18G. H), and the LUSC survival cohort comprised n = 109 patients (24 female, 85 male; mean age = 69.9 years; median age = 70.4 years; Supplementary Fig. 19 G + H).

Step 5 – Visualizations

Feature distributions

All cluster maps were z-scored over columns (features), hierarchical agglomerative clustering was applied with Euclidean distance and single linkage. For better visual contrast, the colormaps were non-linearly compressed with a logarithm, including a multiplicative saturation factor if necessary.

Stacked histograms were sorted based on the one-dimensional projection of their kernel principal components102, done separately for rows and columns. We use a Gaussian kernel with a length scale of one over the number of features. This choice was made to better convey the idea of the multi-dimensional cumulative distribution of the cohort.

The immunology atlas

We embed the tissue spots in a two-dimensional plane to give a comprehensive overview of the concentration and spread among the immuno-composition we found via application of the niches. The location of each spot is determined by the loadings of cell niches measured in each spot. We used a UMAP103 projection with the number of neighbors set to 100, minimum distance set to 8, and a spread of 8. This was chosen to avoid dense clustering that would have resulted in overlapping tissue composition thumbnails. Each tissue thumbnail comes with a circular bar plot that summarizes the niche concentration of each spot. See Figs. 3 and 4.

Ethics declaration

The study was performed according to the ethical principles for medical research of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Charité University Medical Department in Berlin (EA4/082/22). All patients provided written informed consent for the scientific use of their archived tissue and associated clinical data. The study was retrospective and involved no additional procedures or interventions; therefore, no participant compensation was provided. Information on the race, ethnicity and socioeconomic status of patients was not available. Mutation status, recurrence information and smoking status were incomplete at the time of writing.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.