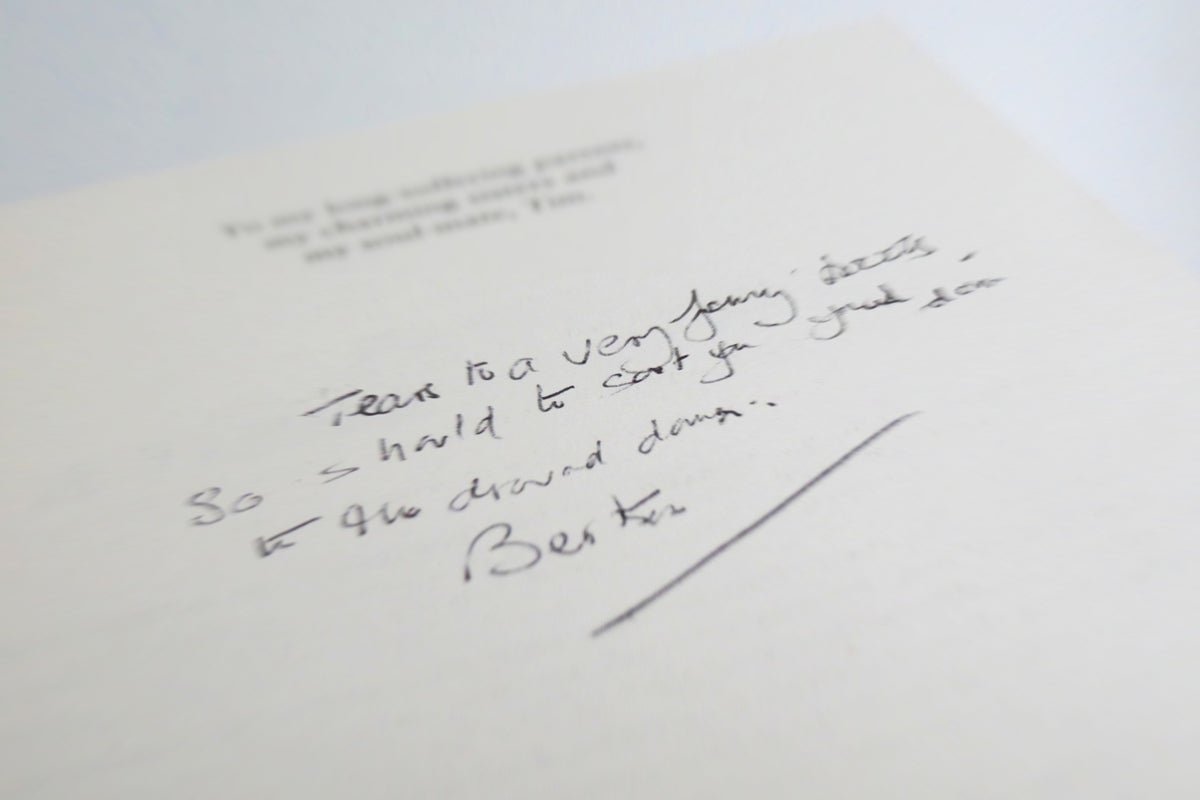

Two days before my dad died, he gave me a book. It was my 28th birthday, and in the front of it was a note, 18 words long, that he had written a few days earlier. But I couldn’t understand it.

I was unable to ask him what it said, as by the time I saw it he was asleep and heavily medicated. Cancer had spread from his brain down through his bones and to his lungs, and the only words I would hear him speak again were “I hope Ireland wins”. (He rose himself briefly from delirious slumber to interject in an argument I was having with my sister across his bed over whether he would want Ireland or France to win the final game of that year’s Six Nations. Ireland won by two points.)

Later, when I showed the note to my mum and my sister, we were able to decipher the first line: “Here’s to a very funny book”, but the rest – the most important part – seemed illegible.

It would be years before I felt ready to actually read the book he had given me, but I kept it by my bedside through several house moves. I would occasionally pick it up and puzzle over those 18 words, and would sometimes show it to close friends or family members, but none were able to offer any further understanding.

The book was Dear Lupin: Letters to a Wayward Son, a collection of father-son correspondences by the late racing journalist Roger Mortimer, and I hoped that reading it would give some clue as to what my own father had been trying to say. The book was indeed funny, as his first line suggested, but the rest of the note remained incomprehensible.

In 2023, seven years after my father’s passing, artificial intelligence tools like ChatGPT began offering the ability to interpret images you upload. They could translate text, or help you understand what you were looking at, so I decided to take a picture of the words and see what it came up with.

The AI immediately recognised that it was a personal inscription, without any prior context, but the words it came up with were gibberish.

Tears to a very funny Dacts

So should to sort ya good down

To the ground dung

Beste

The AI’s explanation was equally confusing. “‘Beste’ is a very common closing in Dutch and German, meaning ‘Best’ or ‘Best regards’,” it told me.

My father spoke neither of those languages, and I knew his nickname to be Bertie, taken from our surname. I also believed the first word to be a misspelling of ‘Here’s’, and the word ‘Dacts’ was almost certainly ‘Book’, so I corrected the AI with my interpretation of his penmanship.

With this new information, it came up with a new decryption of the second two lines.

So should to sort you good down

to the drowned dawn.

My dad was a lot of things – a rodeo rider, a paratrooper, a currency salesman – but he was not a poet. It seemed unlikely he would make his first attempt on his deathbed, with the alliterative final words of the inscription.

But he was an avid reader of poetry, so maybe it was from one of his favourite verses. Nothing came up when I googled those words, and when I asked ChatGPT it came back with this passage:

He walked the shore, down to the drowned dawn,

Where morning’s light lay lost beneath the waves.

When I asked who wrote it, the chatbot apologised for not being able to find “any reliable source attributing the lines”. It was a hallucination.

Not long after, I read about a project involving Google DeepMind, where researchers restored half-destroyed ancient texts by training AI on thousands of ancient Greek inscriptions in order to predict the missing text.

Something like this might work if I had some more handwritten texts that my dad had written in a more lucid state. The only problem was I didn’t have any. The only thing he left me in his will was his substantial book collection, more than a thousand titles in total. Other than one or two first editions, the books themselves aren’t worth much. The real treasure, for me at least, was the bookmarks. Each one was a souvenir of his life: old boarding passes, theatre tickets, business cards, receipts.

I scoured through them all, looking for something he might have jotted down until at last I found what appeared to be a shopping list. In my search I also came across some old birthday cards he had written to me, but in total I had no more than a couple of dozen words. It was not enough. I needed a bigger dataset.

Finally, this summer, there was a breakthrough. It came in the form of a pile of letters written to his sister decades ago while he was working as a jackeroo in Australia. My cousin had come across them and immediately sent them over.

After feeding these letters to ChatGPT and Gemini, the AI was able to analyse his idiosyncratic handwriting style: the looping shape of his consonants and the rushed vowels.

I also provided more context of when and where the note was written, and this was the new interpretation:

Here’s to a very funny book.

So should [help] to sort you going down

to the dismal damp

Bertie

ChatGPT noted that February in Hampshire where he lived, and where I had been increasingly spending time with him, had been the wettest since records began. He also hated the drizzly late-winter in England, so the third line seems like that was definitely what he wrote.

With this success, I decided to try other forms of AI to see if they would uncover any fresh insights into my father. Google Gemini’s new Deep Research feature is able to autonomously trawl through your emails and documents to provide analysis on any topic contained within.

I instructed it to go through any digital interactions I had with my dad, and it came up with a “scholarly analysis of the direct email correspondence between Anthony Cuthbertson and his father, Malcolm Cuthbertson”.

It didn’t offer much more than reading the email exchanges myself could have given. The introduction to the unnecessarily lengthy 3,500-word thesis stated: “The retrieved digital record provides a structured narrative of a father-son relationship set against the backdrop of significant life events, including international travel, high-stakes academic deadlines, philosophical divergence, and terminal disease.”

One thing it picked up on though, which I had never thought about, is that he used his professional email address in all of our personal communications.

“This integration of professional and familial identities suggests that Malcolm viewed his corporate life – the source of his international experience and network – as inseparable from his role as a father, ensuring that his son was privy to both facets of his world.”

But it also missed some of the finer points that it could not know from only our emails. It talked about my “intellectual prowess” after my father congratulated me on my maths A-level result, not knowing that it was a retake, and that I only got a B. It lacks real-world context – a fundamental flaw of AI.

Other AI tools have offered people the opportunity to talk directly with their deceased loved ones through so-called ‘griefbots’ or ‘deadbots’. An increasing number of startups are developing chatbots that use the same large language model (LLM) technology as ChatGPT and Gemini – trained on their digital interactions – in order to attempt to simulate the dead.

I visited an early version of these shortly after my father died, and was unconvinced. They seem to provide more proof that a person is gone, rather than offer any hope that they can be resurrected through a computer.

Others have found these services to be disappointing and creepy, while some have even argued that dead people’s data should be protected from AI by law.

Legal scholar Victoria Haneman argued in a recent paper titled ‘The Law of Digital Resurrection’ that the deceased lack legal protections against their messages, photos and voice recordings being used to create chatbots, avatars or AI versions of them after they die.

“The digital right to be dead has yet to be recognised as an important legal right,” she wrote in the Boston College Law Review, calling for a “time-limited right for deletion of personal data” that gives descendants the ability to destroy all digital archives within a 12-month period.

There may be no amount of digital archives that could provide a fully accurate interpretation of my father’s final words. The second line remains largely a mystery, and that’s OK. I knew the endeavour might be futile. But the search uncovered bookmarks and other relics I might never have found, and helped me understand him in a way I may never understand his final note.

Maybe future iterations of AI technology will help more. Or maybe my dad’s parting words are exactly what they appear to be: a largely nonsensical note, written by a dying, morphined mind offering his son a final birthday present, and a puzzle that can’t be solved.