I’m the type of person who reads the copyright page of books. It’s more of a ritual than anything else; the most interesting thing is usually the printing year, or maybe the publisher.

So imagine my surprise when I open a highly-recommended book, to find this: “Images on pages 45, 91, 149, and 217 were generated by the author using the DALL-E 2 AI system.”

Published in 2023 by Penguin Random House, “Land of Milk and Honey,” is C Pam Zhang’s debut novel. While most people on Earth are suffering from climate disaster, the novel centers on a chef who finds herself cooking for an unfathomably rich family in a community insulated from the dystopia outside.

Inspired by the author’s experience living in the tiny Seattle Eastside suburb of Medina — known for its high concentration of billionaires, including Jeff Bezos and Bill and Melinda Gates — during the pandemic, Zhang and her novel have enjoyed great success, particularly in Seattle. KUOW recently featured Zhang on an episode of their Arts & Culture podcast, and she was the guest of an interview and Q&A with Seattle Arts & Lectures in May.

I had picked up the novel intrigued by the premise and high praise, but was immediately put off by the use of artificial intelligence (AI). Just an inch above the AI acknowledgement was this standard copyright statement:

“Penguin Random House supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for every reader.”

So which is it? Is copyright an essential protection for art and artists, or is it OK to violate as long as you acknowledge it in the small print on a page of the book that no one reads?

Not that it matters, but having read the book, the four images didn’t look particularly special. Similar existing photos or art could have been licensed for use — like the cover was — or even freshly commissioned from artists or photographers. Penguin Random House is one of the biggest publishing companies in the world, and could certainly afford to do so.

Instead, the author chose to use AI. And she isn’t the only one.

The Hugo Awards, arguably the most prestigious science fiction awards in the world, are being hosted in Seattle this year for the first time since 1961. The convention, known as Worldcon, hosts many panels and guests every year; every year, many more people apply to participate than can be accepted, and all of them have to be vetted.

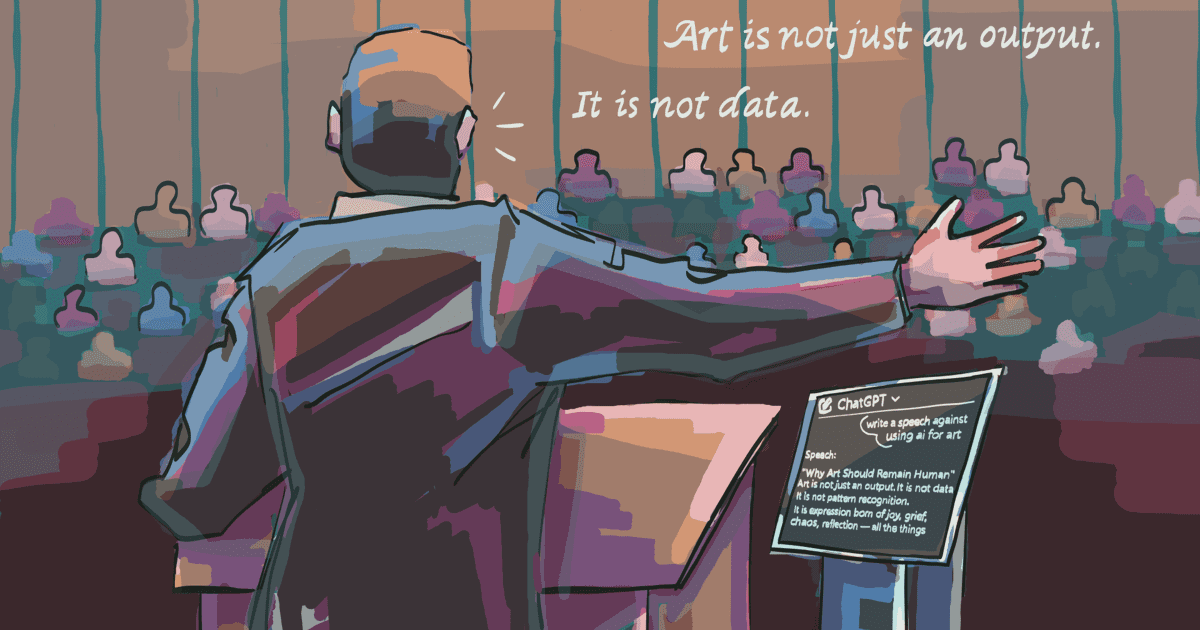

Unfortunately, this year, they chose to do that with ChatGPT. In an attempt to save time, WorldCon organizers submitted a prompt to ChatGPT which included, in part, the following:

“Using the list of names provided, please evaluate each person for scandals. Scandals include but are not limited to homophobia, transphobia, racism, harassment, sexual misconduct, sexism, fraud.”

The prompt was several additional paragraphs long and requested sources, but as we all know, ChatGPT makes things up all the time, including sources. The primary function of ChatGPT is not to search, and there’s no guarantee that any AI is updated with the latest information — certainly not on “scandals,” as they put it.

“We know AI hallucinates — it’s often incredibly wrong,” Olivia Waite, science fiction author and UW alum, wrote in an email. “For me a useful question is: Would you trust AI to write the eulogy at your funeral? Hallucinations look like jokes until they’re misstating your actual life and accomplishments when it counts.

After allegations emerged that organizers had used AI, WorldCon chair Kathy Bond released a statement, explaining that all ChatGPT results were checked by volunteers. As backlash grew, she released several additional statements over several weeks, ultimately providing a long explanation, apology, and stating that WorldCon would redo all work done by ChatGPT. The organization also provided refunds to those who no longer wanted to participate in the convention.

This could have been spotted from a mile away; underpaid and competitive even before AI, writers and artists are some of the most vocally critical of generative AI. Science fiction authors in particular are primed to have concerns about AI, ranging from the decentering of human creativity to concerns about the environmental impacts.

Between correcting AI’s errors and dealing with the fallout, Worldcon would have had less hassle (and fewer resignations) if they’d done the vetting by hand (read: with Google) from the start. How did they not see this coming?

I understand that the AI landscape is changing fast. In fact, since the publication of “Land of Milk and Honey,” Penguin Random House has become one of the many signatories to a statement critical of AI training. It states, “Unlicensed use of creative works for training generative AI is a major, unjust threat to the livelihoods of the people behind those works, and must not be permitted.”

The CEO of Scholastic, another major publishing company, has also signed this letter. Their books — including “Sunrise on the Reaping,” the latest addition to the Hunger Games — now include a line on the copyright page explicitly prohibiting using the book to train generative AI.

They know these models aren’t ethical when it comes to books. But I’m still waiting for acknowledgment by Penguin Random House, or indeed from Zhang herself, that the images in “Land of Milk and Honey,” were made with a tool that used the work of thousands, perhaps millions, of artists without their permission.

Aside from the images, I actually liked the novel. It invites readers to think about the devastating consequences of climate change, the selfishness of stockpiling and wasting resources others need, and the gratification that comes sometimes from doing things the hard way. But to me, these ethical concerns are incompatible with the use of generative AI.

It seems to me that the book industry has a solidarity problem.

“Art is work, plain and simple,” Waite said. “Writers and visual artists should stand in solidarity with each other against predatory tech companies — I wouldn’t steal a painter’s work for my book cover, and they wouldn’t steal my words to sell their paintings, so we shouldn’t let the seeming ease of LLMs and image generators persuade us to do it either.”

Despite their different perspectives and approaches to AI, both Waite and Zhang’s books — and millions of others — have been pirated and used to train AI without permission. But as far as I can see, using generative AI hasn’t made or saved any author’s career. It’s just perpetuating and participating in the devaluation of all creative work, that of writers and visual artists alike.

The only way I can see to stop our work from being fed into the machine would be true solidarity — between artists, and authors, and conventions, and publishing companies, and copyright holders, and anyone else who has ever put their soul on a page.

Take a stand. Have a spine. Don’t use generative AI.

C Pam Zhang did not respond to a request for comment.

Reach writer Chaitna Deshmukh at opinion@dailyuw.com. X: @Chaitna_d. Bluesky: @chaitnad.bsky.social.

Like what you’re reading? Support high-quality student journalism by donating here.