Studies 1–3: Lay beliefs about AI assessing interpersonal skills

Studies 1 to 3 find lay beliefs about AI assessing applicants’ interpersonal skills. Study 1 tested which pieces of information people tend to check when asked to guess whether the applicant had passed the interview assessed by either an AI or human, from four assessment scores (including interpersonal and analytical skills assessment scores). Participants (n = 200) could only choose to reveal one of the four assessment scores and were informed that a bonus would be paid for a correct guess (i.e., incentive-compatible design). Individuals tend to rely on and give more weight to information that aligns with their beliefs43,44. Therefore, if individuals doubt AI’s capabilities to assess interpersonal skills, they may rely on what they perceive as more reliable information. Consequently, participants in the AI (versus human) condition would be less likely to seek interpersonal skills assessment scores than analytical skills assessment scores.

As pre-registered, we compared the proportion of participants who chose to view the interpersonal skills assessment score versus the analytical skill assessment score as a function of assessment agent type. As predicted, the assessment agent type significantly influenced the decision of which information to view (χ2(1) = 19.28, P < 0.001). In the AI condition, 42.7% of participants chose the interpersonal skills score, while 75.3% did in the human condition. The odds of choosing to view interpersonal skills over analytical skills assessment scores were 4.09 times higher (95% CI[2.15, 7.77]) in the human than in the AI condition.

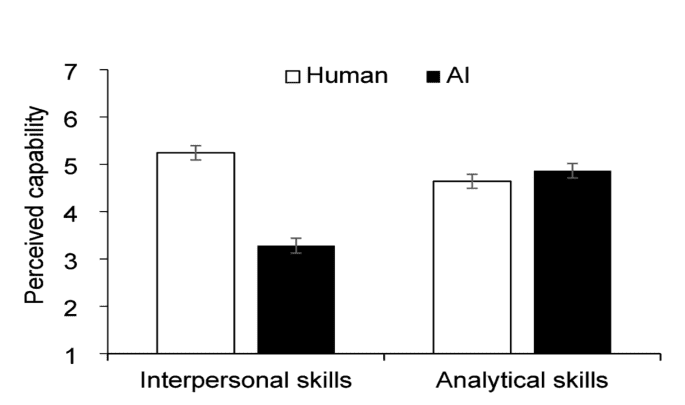

Study 2 tested lay beliefs through another experiment. Participants (n = 201) were randomly assigned to one of two selection processes assessed by either AI or humans. Participants in the AI [Human] condition read a brief description of AI interviewers [HR personnel] and rated the capabilities of the AI interviewers [HR personnel] in assessing job candidates’ interpersonal and analytical skills, respectively (e.g., AI interviewers would be capable of evaluating the job candidates’ interpersonal skills.; 7-point Likert scale; 7 = strongly agree). We expected participants to show less trust towards AI (vs. humans) in assessing interpersonal skills but not analytical skills.

We examined the perceived capabilities of the AI versus human (i.e., assessment agent; between-participants factor) in assessing interpersonal and analytical skills (i.e., skill type; within-participants factor) using a mixed ANOVA. Our hypothesis was supported by the significant interaction effect (F(1, 197) = 93.86, P < 0.001, η2 = 0.323), showing a lower perceived capability of AI (vs. human) for evaluating interpersonal skills but not analytical skills (Fig. 1). Specifically, planned contrast revealed that participants perceived the AI as less capable in the assessment of interpersonal skills (M = 3.28, SD = 1.77) compared to humans (M = 5.24, SD = 1.30; F(1, 197) = 80.07, P < 0.001, η2 = 0.289). However, participants perceived that AI’s capabilities in assessing analytical skills (M = 4.86, SD = 1.60) were comparable to that of humans (M = 4.64, SD = 1.41; F(1, 197) = 1.10, P = 0.30, η2 = 0.006).

We replicated Study 2 (n = 63) using a similar design but replacing the term AI interviewer with AI assessment tools designed to analyze candidates’ responses to job- and personality-related questions and their performance in mini-games2,3. The results were consistent with our earlier findings (see SI 5 for details).

Study 3 (n = 343) explored lay beliefs about AI selection with practitioners by directly asking managers to compare their perceptions about AI and human assessments. We used surveys collected by MidasIT, a major provider of AI selection technology in Korea. Of the participants, 81.6% (n = 280) were responsible for hiring tasks. We focused on two questions asking whether they believed AI or humans were better at predicting an applicant’s interpersonal and analytical skills, respectively (17 indicated definitely AI [human] interviews). We expected managers to believe AI is less effective than humans in predicting an applicant’s interpersonal skills but not analytical skills.

As predicted, managers rated AI as less capable than humans in predicting interpersonal skills (M = 5.02, SD = 1.37; one-sample t-test comparing against 4: t(342) = 13.81, P < 0.001, Cohen’s d (d) = 0.75, 95% CI[0.88, 1.17]), but as more capable in predicting analytical skills (M = 3.44, SD = 1.61; one-sample t-test: t(342) = −6.47, P < 0.001, d = −0.35, 95% CI[−0.73, −0.39]). Next, we estimated a linear mixed model with a random intercept and slope for each manager, where we regressed managers’ lay beliefs on each of the two assessed skill types while controlling for their involvement in hiring tasks (i.e., by adding fixed effects for a dummy variable indicating whether each respondent was in charge of hiring tasks or not). The results showed the same pattern of significance (b = 1.58, t(342) = 14.88, P < 0.001, 95% CI[1.37, 1.58]).

Studies 4–5: Consequences of lay beliefs about AI assessing interpersonal skills

The previous studies suggest people negatively perceive AI’s capabilities in assessing applicants’ interpersonal (vs. analytical) skills. Studies 4 and 5 examine the potential consequences of these lay beliefs for office workers and job applicants. Study 4 tested whether office workers hold biases towards AI-selected employees as opposed to those selected by humans. If office workers are skeptical of AI’s capabilities in assessing interpersonal skills, they might also perceive AI-selected employees as having inferior interpersonal skills than those selected by humans. As a result, we predict that office workers would be less likely to assign tasks requiring interpersonal skills to AI-selected employees (vs. human-selected), but this bias would not extend to tasks requiring analytical skills. That is, we predict that office workers would not assign tasks requiring analytical skills more to employees selected by humans than AI.

We recruited 102 office workers in large Korean companies, which are increasingly using AI assessments. From the managers’ perspective, the office workers evaluated two hypothetical employees, one hired through a conventional HR interview and the other hired through an AI interview. Participants were then asked to indicate which employee they would assign tasks requiring interpersonal skills and analytical skills, respectively (i.e., using a 7-point Likert scale where 17 indicated a definite preference for the HR [AI] interview hired employee).

As predicted, the office workers indicated that they would assign tasks requiring interpersonal skills less to the employee hired through the AI interview than the one hired through the human interview (M = 2.55, SD = 1.36; one sample t-test with a comparison against 4: t(101) = −10.76, P < 0.001, d = −1.07, 95% CI[−1.72, −1.18]). However, they were more likely to assign tasks requiring analytical skills to the AI-interviewed employee (M = 5.29, SD = 1.41; one sample t-test: t(101) = 9.26, P < 0.001, d = 0.92, 95% CI[1.02, 1.57]).

Study 5 tested another potential consequence of the lay beliefs, focusing on applicants’ strategies during the selection process assessed by AI versus humans. We investigated which type of skills is considered important for each of the two selection types. Given that people’s behavior tends to reflect their beliefs43,44, if job applicants are skeptical about AI’s capabilities in assessing interpersonal skills, applicants may infer that showcasing these skills will have less impact on the selection decision. Consequently, they should emphasize their interpersonal skills less in the AI-assessed selection process than in the human-assessed one. Conversely, we anticipated no such difference for analytical skills.

We recruited 107 participants from South Korea, who had experienced a selection process evaluated by both AI and humans. We asked participants to recall their most recent interviews of each type and then to indicate in which of the two interviews they had emphasized their interpersonal and analytical skills relatively more (where 17 indicated they definitely emphasized the skill more in the human [AI] interview; the order of the two skill questions was counterbalanced, which has no significant effects on participants’ responses (all p-values > 0.4; SI 6)).

As predicted, participants emphasized interpersonal skills less during the AI interview than human interview (M = 3.31, SD = 1.67; one sample t-test against 4: t(106) = −4.28, P < 0.001, d = −0.41, 95% CI[−1.01, −0.37]). On the other hand, participants emphasized analytical skills more during the AI interview than human interview (M = 4.42, SD = 1.51; one sample t-test against 4: t(106) = 2.88, P = 0.01, d = 0.28, 95% CI[0.13, 0.71]).

Study 6: Alleviating negative lay beliefs about AI assessing interpersonal skills

The previous studies highlight negative lay beliefs about AI that could cause problems in organizational settings, affecting managers’ task assignments and job applicants’ strategies during selection processes. However, our field data analysis suggests that AI selection technology can outperform humans in predicting interpersonal performances. Likewise, research continues to demonstrate the efficacy of AI in measuring interpersonal traits, such as friendliness26,27,28,29. Therefore, Study 6 investigated a strategy to reduce the negative lay beliefs about AI assessing interpersonal skills. We speculated that people may find it challenging to grasp the concepts of AI technologies being used to assess interpersonal skills. Therefore, we predicted that informing people of various examples of recently developed AI selection technologies that can assess interpersonal skills would help reduce the negative lay beliefs.

To test this, we recruited 231 participants who had heard of AI selection technologies to examine the change in consumers’ existing beliefs toward AI’s capabilities. We told participants that they would take on two supposedly unrelated tasks. In the first task, participants were randomly assigned to one of the two conditions—AI-information vs. control condition. Participants in the AI-information condition summarized a news article about the trend of AI selection technologies that capture facial expressions, emotions, social skills, and more, while those in the control condition summarized a news article on the use of AI in separate contexts. For the second task, participants were asked to evaluate which type of the two selection processes would be more effective in selecting applicants with outstanding interpersonal and analytical skills, respectively (where 17 represents definitely more effective in human [AI] interview).

As in Study 2, participants in the control condition thought that AI was less effective than humans in selecting applicants with outstanding interpersonal skills (M = 2.63, SD = 1.56; one sample t-test: t(114) = −9.42, P < 0.001, d = −0.88, 95% CI[−1.66, −1.08]); however, they thought AI was more effective for selecting applicants with outstanding analytical skills (M = 5.16, SD = 1.47; t(114) = 8.46, P < 0.001, d = 0.79, 95% CI[0.89, 1.43]). Using a mixed ANOVA, we then tested whether informing participants about advanced AI selection technologies would increase their perception of AI (vs. humans) in assessing interpersonal skills, but not in terms of analytical skills (Fig. 2). As expected, the interaction was significant (F(1, 229) = 7.67, P = 0.01, η2 = 0.032). A further breakdown of this interaction showed that the perceived capabilities of AI assessing interpersonal skills were higher in the AI-information condition (M = 3.28, SD = 1.67) than in the control condition (M = 2.63, SD = 1.56; F(1, 229) = 9.34, P = 0.03, η2 = 0.039). By contrast, the perceived effectiveness of AI in assessing analytical skills did not differ significantly between the two conditions (MAI−information = 5.16, SD = 1.47 vs. Mcontrol = 5.08, SD = 1.32; F(1, 229) = 0.19, P = 0.67, η2 = 0.01).