Author’s note: This is a personal reflection about name, memory, and my own journey toward Judaism. It is not a critique of Islam or of anyone who bears the name Mohamed; I write with respect for my family and their traditions. Any discomfort I describe concerns the mismatch between a given name and my inner life, not the faith that name represents for others.

I was six years old the first time I heard it. “Mohamed * * *,” the teacher called out, her voice cutting through the classroom like a hammer striking glass. I remember looking around, confused. Who was this boy she was summoning? I didn’t recognize him. I didn’t stand up. My small hands clenched the wooden desk as a hundred eyes turned toward me. That was the moment I first confronted the ghost that would haunt me for the rest of my life: my legal name.

At home, I was Soncino (a nickname from my grandmother). I was the beloved grandson, the curious dreamer, the boy who believed in magic and stories, raised by my grandmother’s warmth. At home, the name “Mohamed” didn’t figure into our daily life; our family identity was cultural, not religious. But in official life, on every piece of paper, at every border, there was that name. It followed me like a shadow. It wasn’t just a name. It often felt like a weight I hadn’t chosen. I didn’t grow up with formal religious practice, and faith wasn’t part of my upbringing. My family roots suggested another story of quiet resilience and hidden identity. My grandfather’s family came from Morocco, settled in Tunisia, and carried traces of Jewish life they rarely spoke of. My grandmother never mixed milk and meat in her kitchen, a custom she kept without even knowing why. These fragments of tradition, like sparks under ash, whispered to me about a heritage that had been obscured, about ancestors who had to hide or change to survive. That name, Mohamed, was something I never chose. It felt like an imposition that buried parts of me I hadn’t yet discovered. My own identity felt suppressed beneath a name that was never truly mine.

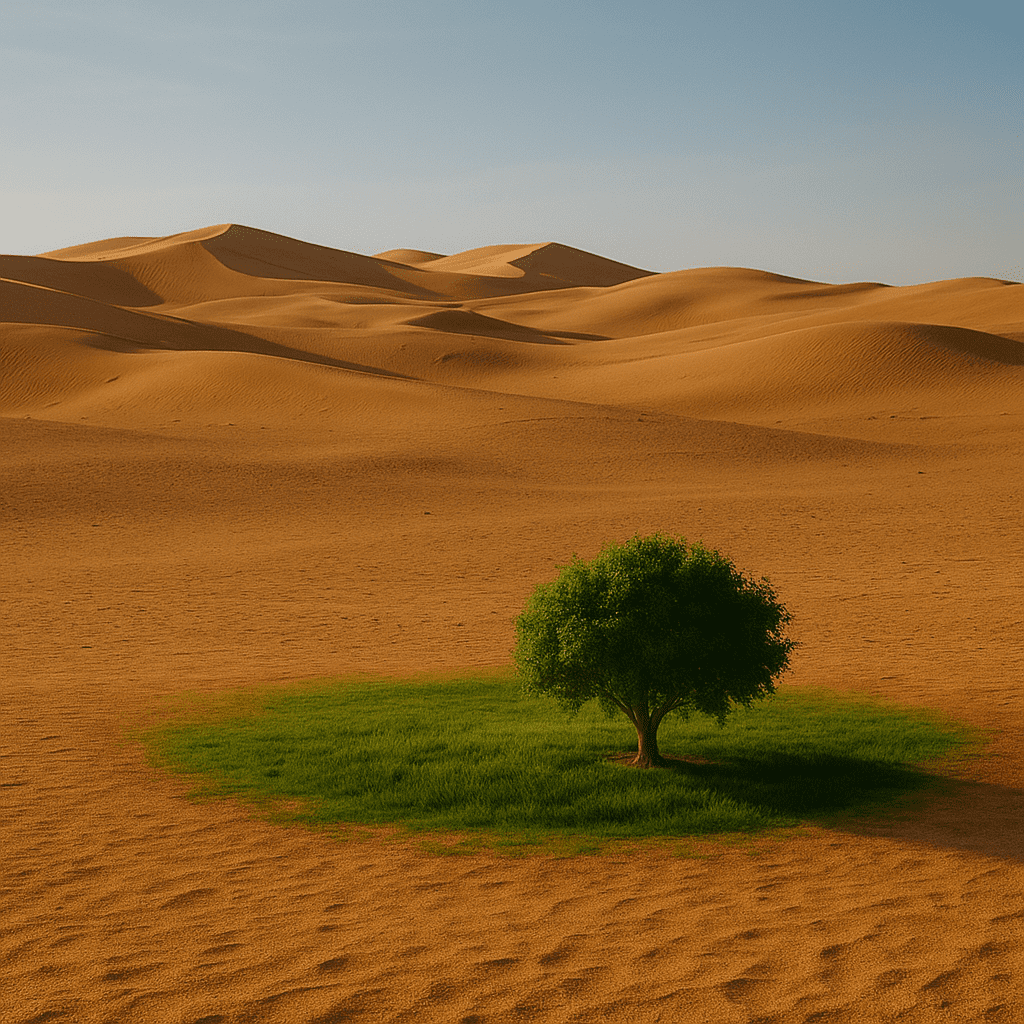

When I moved to Turkey, the ghost came alive again. People called me “Mohamed,” each syllable landing like a reminder. To them, it was just a word. To me, it was a daily reminder of loss, of a lineage that could have flourished in the open, of a soul that longed to return home. Names are supposed to be mirrors of the soul. For me, my legal name has always felt like a mask I couldn’t wear comfortably. Then came Eden. Choosing Eden wasn’t about aesthetics. It was about liberation. It was about reclaiming a spiritual inheritance that had been hidden, reconnecting to the Jewish spark that flickered in my family stories and in my own heart since I was a child. Eden is my garden after years in a desert. It is the name that holds my grandmother’s warmth, my grandfather’s hidden prayers, and my own yearning for rebirth.

I was maybe six or seven, sitting at my grandmother’s table in Tunis, eating a palmier; those flaky French pastries that taste like someone baked a hug. She brought them to me every day after school in a little paper bag, always with a glass of milk or a splash of coffee depending on the day. We would sit down around 4 p.m., as if we were in a Parisian salon and not in the heat of Tunisia, and just be. It was our ritual: cake, coffee, calm. No rules, just elegance. Until one day, I asked for meatballs. To my surprise, she said no. Not right after milk. She didn’t yell or make a scene. She just said very casually, “We don’t do that, honey.” I didn’t understand, since we didn’t “do” or “not do” anything in our home. But there were rules, quiet and mysterious ones. That moment over meatballs and milk would come back to me years later like a ghost with a message. My grandmother raised me. She was beautiful, different from other grandmothers, more like someone out of a 1960s French film than a woman in a traditional Tunisian home. She wore dresses just to go to the corner. She spoke three languages. She never left the house without perfume or lipstick. She was stylish, dramatic, self-composed, a little theatrical, and completely in control yet always warm. She never sent me to religion school. I wasn’t raised with formal Islamic instruction; I first encountered it when I saw classmates attending Qur’an lessons. Meanwhile, I was at home learning how to drink coffee properly and hold a conversation like a little diplomat. I didn’t know faith, but I knew flair. When I was twelve, I made a kippah myself, carefully, with my own hands. I wore it to school in Tunis, proudly, like a secret crown. Other children destroyed it. They burned it. I watched it burn. I didn’t cry this time. I just watched, feeling something ancient inside me scream, a voice I didn’t yet know, echoing from ancestors who were forced to hide or vanish.

My grandmother died when I was ten. But not really. She left, yes, but not her scent, not her rituals, not the way she poured coffee like it was sacred. She left me her memory, her style, her standards, the way she carried herself like royalty even in a tiny kitchen. Years later, my aunt passed while I was living in Istanbul. I couldn’t come home, couldn’t say goodbye. But she didn’t leave either. She left me her etiquette lessons, her way of walking through the world with posture and pride. They both live in me, in how I dress, in how I speak, in how I sit at 4 p.m. and think, I should really be having cake right now. They weren’t religious, but they were sacred. They were strong, elegant, independent women, and they raised me to be the same. And then there’s my mother. She didn’t give me religion, not hers, not mine. But she gave me something better: freedom and love. She made the intellectual in me. She taught me how to think, how to ask questions, how to never shrink. She has been my greatest support. Even when she doesn’t fully understand my spiritual journey, she supports me without conditions. Maybe she didn’t give me her faith, but she gave me her strength. And I carry her in every version of myself that dares to search, speak, and rebuild.

Now, I’m 29. I wear a kippah again. I study Jewish texts. I light candles. I say blessings. I don’t think I’m converting. That word feels too external. I think I’m remembering. Lighting the candle someone blew out generations ago. Speaking the name someone buried for safety. Singing a melody I had never learned yet somehow knew by heart, like a lullaby waiting for me all along. I’m not fully observant and not (yet) halachically Jewish, but I’m deeply Jewish in ways no paperwork could ever explain. And that’s the kippah I wear.

Eden Taboubi is a graduate in political science and international relations. Raised between cultures and borders, he writes opinion essays at the intersection of identity, Zionism, and diaspora politics, exploring Israel and Jewish life as part of a personal journey to reconnect with roots and reflect on contemporary debates.

His work on this platform represents personal views and reflections, not academic research, and is written in the style of public commentary rather than scholarship.

Professionally, Eden has worked in international marketing, foreign relations, and innovation-focused education, with experience across NGOs, startups, and cross-border projects. He brings a Mediterranean perspective to global issues, blending academic training with practical experience in diplomacy, advocacy, and intercultural dialogue.