More than 300,000 women ages 18 through 44 live in an area that

doesn’t have enough hospitals or birthing centers – or in in some cases, any at

all. That’s according to data from the March

of Dimes.

Researchers at UNC-Chapel Hill are using AI technology to

provide more resources for expecting mothers.

“There are plenty of places in North Carolina that don’t

have adequate access to ultrasounds,” said Dr. Jeffrey Stringer. “It’s very

difficult to provide obstetrical care without an ultrasound.”

Stringer is an Obstetrics and Gynecology Professor at the

UNC School of Medicine. He and his wife, who also works in the field, first

noticed a need while working in Zambia for eleven years. Fast forward to 2025,

and Stringer is hoping to get technology in clinics and hospitals by the end of

the year.

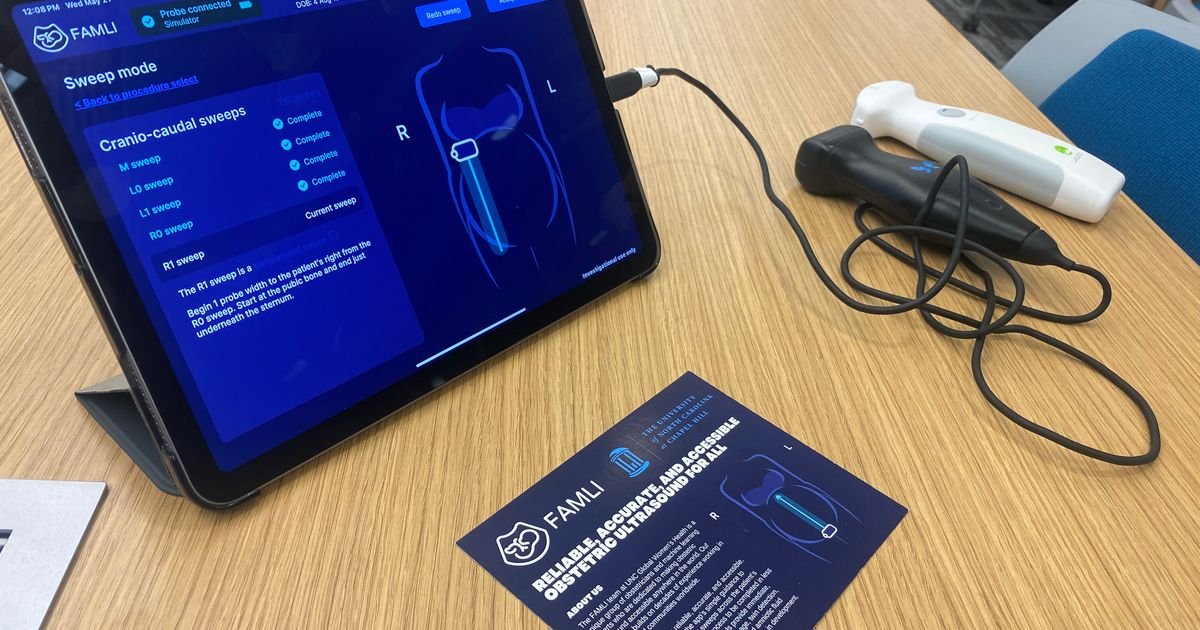

Research project manager Srihari Chari helped develop the

FAMLI app. Users plug in battery-powered ultrasound devices into a smartphone

or tablet. The app then guides the user through the ultrasound to collect data,

including the age, size, and position of the baby.

“On the results screen, if there’s anything that might be

concerning, we include a little yellow exclamation point,” Chari explained.

“It’s not meant to be alarming to the patient. It’s just to say, ‘Hey, this

patient might need additional care.’”

Stringer said the goal is to be able to increase its

capabilities to diagnose more in the future, like certain birth defects or

ectopic pregnancies, which are life-threatening.

“The functions that we have built into the app right

now are probably not sufficient to replace all of the ultra-sonography that’s

going on in remote counties in North Carolina,” he said.

WRAL asked how accurate the AI results have been so far.

“The AI is actually more accurate than an expert

sonographer, using one of those more expensive machines…We know that from

clinical trials that we’ve done,” Stringer responded. “It does get it wrong,

sometimes. That’s why we’re continuing to work with the technology to try to

continually make it better and build in fail-safes…It’s an evolving

technology.”

Stringer said the product is the result of more than 7 years

of research and $20 million from various grants.

“I don’t tell the AI what to do. I collect tons of information,

and I say, ‘here are some examples’…and the AI, itself, learns to distinguish

among those… To do that, you need gigantic amounts of data,” Stringer said. “By

far, the most expensive aspect…is collecting this type of data.”

Right now, the app is only being used for research purposes.

However, the team has several applications in to get approval from the U.S.

Food and Drug Administration. First, Stringer hopes to make the technology

available in medical settings, particularly in more rural counties that don’t

have obstetricians or obstetrical care.

“Some women have high-risk pregnancies that need to be

monitored frequently,” Stringer said. “We’re trying to do is build the AI tools

that allow providers who don’t have formal training in sonography to use them

competently.”

He eventually wants people in the community to have access

to technology, like doulas or even parents themselves.

“There is an idea that we’re working on, that we’re not as

far along on, which is, is it possible for patient themselves to use this?” Stringer said.

He said the app is not meant to replace medical staff

but instead, free them up to address more complicated cases.

“Our goal is not to replace the expert sonographers

who are doing these detailed anatomy scans…We’re trying to build a

simple tool that can be used at the lowest level of care as a screening

modality that allows patients to get early, accurate results and avoid having

to drive 2 and a half hours,” he explained.

Not only would the app provide more accessibility to

parents, but it would also help hospital systems save time and money on

ultrasound equipment.

“[The app] takes 2-3 minutes to collect the data and produce

the diagnoses,” Stringer explained. “That’s very different than having to make

an appointment and having to drive to get a normal ultrasound.”

WRAL found that battery-powered ultrasound devices range

anywhere from $50 to $5,000. Full-sized machines that could be found at

hospitals can cost up to $50,000, based on WRAL’s search.

Stringer and his team are also testing the product in

developing countries, with the hopes of increasing accessibility there, too –

including in Zambia.